Elements 31: Gallium

(..)

On scientific content as artistic inspiration

“The new BIG STORIES are all told by science, their scope is vast, and their telling has only begun relatively recently. We are daily getting updates on answers to all the ancient basic questions of life that inspired human art, cultures, and religions for millennia, and we are getting verifiable answers this time. Most important is perhaps that we are also facing completely new questions.

It is high time the old myths and beliefs are abandoned and replaced by contemporary, that is to say: scientific sources of information, imagination, and inspiration. The vast field of modern science is far more complex, has a verifiable and direct relation to reality, and it offers a far greater abundance of possible stories and references for artists in all disciplines than any older belief or myth system, however poetic, could ever come up with[1].

In our times we need new and innovative operas and symphonies, whether electronically or no; let these forget the simpler stories of our past and use these new narrative sources of our present and future for reference and inspiration.”

–Oscar van Dillen

(…)

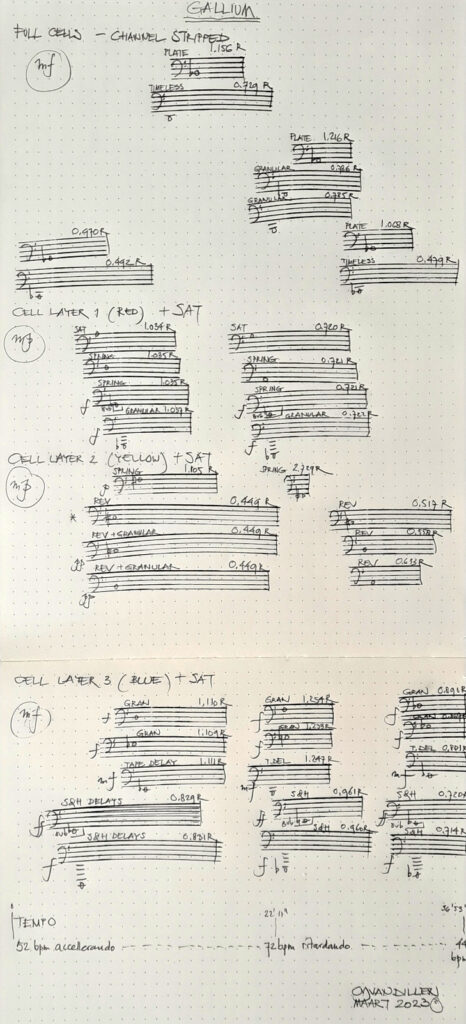

The process of electronic composition can be so complex that often notes and partial scores or particellas while working can be needed to keep a full overview of the work in progress, to retain the full freedom to compose and change. For this purpose van Dillen developed his graphical scores using a Stravigor, made in Barcelona.

A particella like this could also be used as an intermediary step to create a faithful instrumental and acoustic version of the same work, a precise instrumentation of what was originally a purely contemporary electronic work. It of course contains selected information only.

Much more than with instrumental composition, the process of electronic composition is often (though not always) directly in sound, just as a sculptor and painter work: not by making graphs and plans like architects do, but directly working in the matter itself. The electronic work in progress is continually heard and evaluated, then developed and changed, and heard again, re-evaluated, et cetera. During instrumental composition the real sound is always imagined on the basis of perhaps tones played on the piano, which may also limit the imagination to merely the well-known frequencies and pitch classes. While composing complex works containing polyrhythmic or microtonal passages van Dillen advises to always sing (“electronic solfege” would embody “singing” what you create and creating what you sing):

“if you want it you should write it, but you have no real license to write it as long as you cannot sing it, so learn to sing what you want to write before you write it, certainly before you print it”.

read more on www.oij-records.com